Digestive System

In a basic sense, food gets deconstructed as cells that get reconstructed to build you. Digestion involves the proper breakdown of protein, fat and carbohydrates which are required to be absorbed correctly into the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

The digestive process begins with the cephalic phase of digestion, before food even enters the mouth. It begins when your senses are triggered: You're cooking a delicious meal. You hear the crackle of garlic browning in the pan, the smell drifts through the kitchen as it cooks. Maybe you sneak a taste of the sauce as you go. Your senses stimulate the cerebral cortex of your brain, your hypothalamus and medulla oblongata which in turn prepare the body for digestion by stimulating the secretion of saliva and mucus. Beyond this, there are several other, more obvious components to the process of digestion:

- Ingestion: Taking food in, usually through the mouth, chewing & swallowing

- Mechanical Digestion: The physical actions of breaking down the food into smaller pieces, which includes chewing in the mouth and churning in the stomach.

- Chemical Digestion: Large molecules are broken down into smaller molecules, separating into carbohydrates, proteins & fats.

- Absorption: The taking up of nutrients into the bloodstream to the liver.

- Elimination: The removal of undigested and unabsorbed foods.

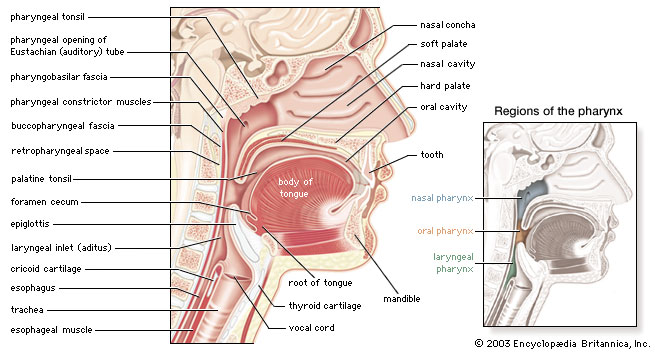

Mouth / Bucal Cavity & Pharynx

You take a bite and begin chewing the food, breaking it into smaller pieces (process of mechanical digestion) and the food mixes with salivary amalayse that has been secreted by three sets of Salivary Glands: the Parotid (just below the zygomatic arch, Sublingual, and Submandibular. The salivary amalayse, a form of chemical digestion, begins breaking down starches into sugars. Here in the mouth when the food mixes with the salivary amalayse, it takes on a new name: bolus.

Swallowing is your last conscious participation in the digestive process. You press your tongue against the soft palate of your oral cavity allowing the bolus to enter the pharynx (throat) which triggers the epiglottis (a little trap door) to cover the trachea (windpipe) so the bolus can travel down the esophagus.

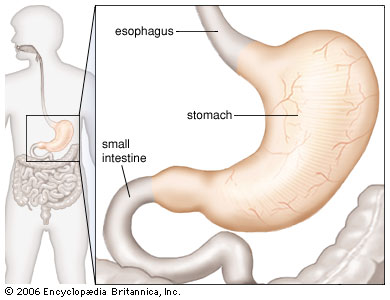

Esophagus & Stomach

The esophagus is long and lanky, about 10 inches, and is lined smooth muscles, some of which run in spiral patterns which allow for elasticity. The bolus is propelled down the esophagus via peristalsis, the rhythmic contraction of those smooth muscles. If you have ever swallowed too big a bite and felt the food sort of get stuck, but after a second or two, you it move along, that is the peristalsis at work.

The stomach lies in the upper part of the abdominal cavity–much higher than we think. It starts below the left nipple and ends near the bottom right rib. It has the shape of the letter J and when empty is about the size of a large sausage. The bolus passes through the lower esophageal or gastroesophageal sphincter and into the first part of the stomach, the cardia. The bolus moves through the cardia and into the fundus and the body of the stomach. Here, mechanical digestion continue as the oblique muscles, unique to the stomach, knead and churn the food.

Chemical digestion continues in the stomach too. The stomach's mucosa contains gastric glands that have secreting cells: parietal cells which secrete Hydrochloric acid that kills bacteria entering the body through food; and chief cells which secrete pepsinogen the inactive form of pepsin. The hydrochloric acid activates the pepsinogen into pepsin which begins the digestion of proteins. But, as you might know, hydrochloric acid can be very corrosive, so the stomach has a protective mechanism. Mucous cells secrete mucus that protects the stomach wall and also helps food digest and move through to be eliminated. Together, all these secretions are called gastric juices and when these juices mix with the food, instead of bolus it takes on a new name: chyme. The chyme passes through the pylorus of the lower stomach, by way of the pyloric sphinctor and into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine.

Small Intestine

The small intestine winds around in our abdominal cavity for a distance between 10 and 20 feet. Inside it is moist and pink and has a velvety appearance. Each square inch of the small intestine's surface contains something like 20,000 microscopic fingerlike projections called villi and on the villi even smaller microvilli, the purpose of which is to increase the surface area of for digestion and absorption. In fact, the total surface area of our digestive system is something like a hundred times greater than the surface area of our skin.

The final breakdown of the food we eat takes place in the small intestine along with the help of accessory glands and organs like the pancreas, liver and gallbladder which secrete juices and bile to break down protein, fat and carbohydrates. Once broken down into small enough molecules, the capilaries on the ends of the villi are able to transport the nutrients through the gut wall, into the bloodstream and to the liver where harmful substances and toxins are removed before the nutrient-rich blood enters the main circulatory system.

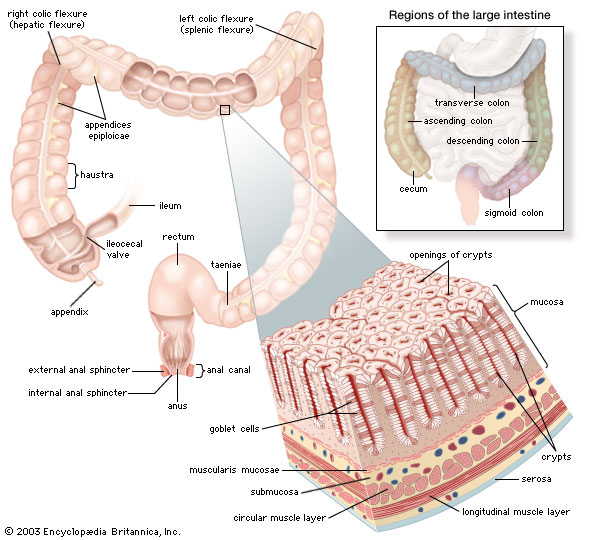

Large Intestine

The large intestine is approximately 5 feet in length and averages 2.5 inches in diameter and forms a frame of sorts around the small intestine. While the small intestine is responsible for the majority of digestion of your food and the absorption of key nutrients, the colon does more than house feces. Through back-and-forth motions of haustral churning, the large intestine makes the most of the leftovers absorbing remaining nutrients–notably calcium which can only be absorbed properly here– and is home to an array of intestinal flora with very important roles. Bacteria in the colon manufacture:

- Energy-rich fatty acids

- Vitamin K (needed for clotting)

- Biotin/vitamin B7/vitamin H (needed for glucose metabolism)

- Vitamin B5 (needed to make certain hormones and neurotransmitters)

62 Veg Caps. BIOME-XYM™ is a blend of thirteen (13) broad-spectrum super strains of probiotic bacteria that originate from six (6) different genera or families. They are delivered to the lower intestinal tract via delayed-release, acid-resistant capsules. Each dosage contains 50 billion CFU. This product does not require refrigeration.